Maybe I haven’t gotten wiser as I’ve gotten older

Last week, I had the chance to drink hot chocolate and catch up with my friend Karen who made me start to question something I had taken as fact. Those, of course, are my favorite kinds of conversations.

Over the past two years, I’ve done a really good job of divorcing my self-worth and self-identification from my job. (Don’t get me wrong: I absolutely adore my job, and feel incredibly lucky and blessed to be able to do the work I do and to do it with such an amazing group of people.) Working in public service is part of who I am; working in service of the public is an even bigger part of who I am. When people ask me what I do, I’m very quick to say that I support people who do the work of making our city, our province, our country, and our world better; this just happens to be my day job as well, but it also guides everything I do in the community, in my family, and every other part of my life.

It wasn’t always like this: it took many years for me to come to terms with not finding my self-worth in my work, but in myself and in my interactions with others. Even until two or three years ago, my definition, my “what do you do?” answer came from my job. I chalked up my recent transformation, my change in perspective to age; that as I’ve become older, I’ve become better at understanding who I am.

That’s where the conversation with Karen shook me from this paradigm. What if, instead of age, my propensity to self-define outside of my occupation is actually due to where I work?

Her argument was simple: by not walking into an office every day, by not entering a physical building that says “work” on it and instead being able to perform my occupation from places around my community, I’m able to intertwine my work life with my community life with my family life. When your “office” is your kitchen, your local coffee shop, a co-working space, the tables at the market, and sometimes, occasionally, a cubicle or office building, perhaps it’s easier to see yourself as part of a multitude of spaces, rather than in one—physically and metaphorically.

I’ve been attributing my perspective to age—I’ve been telling myself that my broad self-definition has come to me because I’m getting older—but perhaps I should be attributing it to place.

Maybe I haven’t gotten wiser as I’ve gotten older, but instead I’ve just found new spaces in which to exist.

In case you missed it:

- On the one-year anniversary of the horrific Mosque Shooting in Quebec City, I wrote a stream-of-consciousness reflection of how I feel being a Muslim in this country.

- The theme for the most recent edition of The Mixtape Concern was déjà vu, so I created a fun mixtape focused on songs that sample other songs.

- I watched Call Me By Your Name and was enthralled by the end credits and everything they meant.

A few things to read and explore:

Before you read anything else this week, make sure you read this interview with Quincy Jones in Vulture where he dishes dirt about everyone he knows and drops more f-bombs than you’d expect. Do you like Brazilian music?

My list of podcasts to listen to grows every day; at this point, I almost feel a kinship to some of the long-lasting ones. As Glen Weldon articulates, I’m not the only one that feels the intimacy of podcast listening:

Listening to a favorite podcast — whether you do it over the course of years, months or hours — engenders a powerful sense of intimacy. You come to know the hosts’ tastes, their tics, the phrases they overuse. As they unthinkingly dole out tiny, incremental parcels of information about their personal lives — a new baby here, a beloved pet’s passing there — you realize one day that your brain has unthinkingly constructed exhaustive virtual dossiers on each of them.

You listen to them talk to one another in exactly the same way you talk to your friends. You keep them close throughout your day — you can even sleep with them if you want to, that’s your business.

Perhaps most crucially, earbuds transmit their voices inside your head — they roost there, rubbing shoulders with your own thoughts.

I can spend hours gushing about the public library, but in short, this article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette captures it perfectly: the public library is a most democratic place:

There is almost no building other than a library where everyone is free to sit down without need for money or an explanation. It’s comforting to be among other people without obligation.

So many policies and campaigns about safe streets are focused on pedestrian habits, without realizing that the big problem is the fundamentally unsafe design of our roads:

“Distracted pedestrian” laws aren’t really about the evidence, though. They are about maintaining the privileges of car culture as that culture is about to confront an enormous shift in the balance of civic and technological power—one that threatens to permanently upend the relationship between drivers and pedestrians. […]

As it turns out, when cities are safer for pedestrians (even the distracted ones), they are safer for everyone. The U.S. cities with the lowest rate of traffic deaths tend to also be cities where pedestrians are common and driving is a pain. Aggressive enforcement of jaywalking ordinances will never solve what is ultimately a problem of road design.

I wonder just how much the subtle daily racism I face (yes, daily) contributes to my depression and anxiety disorder. Not many people talk about it, but racism is wreaking havoc on our mental health:

That’s why it’s so important to remember that in moments of racism, those are traumatic moments and … either we’re not willing to or we don’t have the capacity to deal with that. When an incident happens today, you might not process it … some people are so fast to say, “Oh, there goes that angry coloured girl again.”

And so they say that was a disproportionate response to that small thing that happened on the subway or on the bus. But actually, when you think about it, [she] might not just be reacting to what happened today, but the incident that happened 10 days ago, or 10 months ago, or 10 years ago, or the very first moment, and it’s compounding impact, because you’re re-living it.

The piece around racism that is so insidious is that it’s constant, and the piece around unlearning these things and supporting people in those moments is that validating someone’s experience of racism is so important.

I’ve been fascinated to watch the best critical voices of our generation grapple with the horribleness of many of the people we previously admired. This rumination on Woody Allen by A.O. Scott was insightful in many ways, especially as he addresses the idea that there is no separation between artist and art, but that “art belongs to life:”

“The separation of art and artist is proclaimed — rather desperately, it seems to me — as if it were a philosophical principle, rather than a cultural habit buttressed by shopworn academic dogma. But the notion that art belongs to a zone of human experience somehow distinct from other human experiences is both conceptually incoherent and intellectually crippling. Art belongs to life, and anyone — critic, creator or fan — who has devoted his or her life to art knows as much.”

In my effort to be kind to myself, I am learning when to reach out and ask for help when I am struggling. That might be why this piece by Anne T. Donahue about asking for help resonated so much, even if it was referring to unfuckwithable women:

I, contrary to what I’ve claimed and told myself, need people. I need help sometimes. I need moral support from friends and family, I need a therapist, and I also need to be on medication that keeps my brain balanced. I, an independent person who values alone time, still needs a support system. And while we’ve painted a generation of women as unf-ckwithable because they don’t seem to need anybody, we’re wrong. As someone who works at home, I’ve carved out a career that’s lent itself to operating on my own terms, I’ve also put myself in a position where I can spend days in my apartment without talking to another person, minus neighbours in the elevator. And that isn’t great when you’re stuck in a January-shaped bell jar and need someone you know and trust to push you out with much-needed honesty. Or to sit next to you when you open up about how too-much everything feels. You’re not a martyr by maintaining the guise that you’re weak or any less of a boss if you can’t take it all on alone. You don’t earn more points by making it difficult for yourself.

I fought very hard to get electoral reform to come to our city, and even though we’ve formally adopted ranked ballots for the next election, people are still mad at me for fighting for change. I think reform is necessary if we want a more equitable electoral system, as these short ruminations on city without anti-Black racism describe:

The way our political system is structured right now benefits the incumbent. There’s no incentive to reach out to those in the community who are systemically marginalized. Politicians need to ensure their presence in communities, and we need to ensure we’re holding them to account. They can’t just show up every four years and bank on the same people to elect them in again. We need to keep the pressure on, and that’s why it’s important to support the work of activists on the ground who are pushing for that change so that those on the inside can push for that change as well.

I’d like to see a change in our electoral system. Ranked ballots are very interesting. People are forced to think more critically about who they want in office when they’re required to rank the individual as opposed to just choosing one. I think there’s an incentive for people to actually come out if they feel their vote carries more weight.

For years, police now suspect, a serial killer has been targeting queer men in Toronto. Anthony Oliveira writes a haunting, heart-breaking rumination on a community that has been stigmatized and whose safety has been ignored by those tasked to keep us safe.

In the heart of the village, behind the 519, in the park across from Tess Richey’s alleyway memorial, you will find a bank of roses, and among them on plates a list of names. These are Toronto’s dead, lost to AIDS, when no one in power cared to act, when the old boys’ network raided the bathhouses and the parks and the bars.

In the summer we hold a vigil, and by candlelight we recite their names, and we recite the names of those killed at the Pulse massacre, and we recite the names of anyone else who was loved and lost. This year we will recite new names.

Their names were Selim Esen. Skandaraj Navaratnam. Majeed “Hamid” Kayhan. Abdulbasir Faizi. Sorush Marmudi. Dean Lisowick. Andrew Kinsman. Alloura Wells. Tess Richey.

There are more names. There will be more names still.

And we will forget some. And we will not know how many died in silence and in secret and alone. No one will tell those stories. No one will know how.

My friend Kate N, with whom I went to high school, lives in Atlin, BC with her partner Kate H, who recently wrote a travel memoir that is getting a lot of buzz and looks like the kind of travel book I’d love to read. Can’t wait to get my hands on it—in the meantime, this interview with Kate H in Hazlitt is a wonderful look at the behind-the-scenes world of travel writing and publishing:

I’m less interested in truth, though—whatever that is—than in being aware, at all times if possible, of the wildness of being at all. Goethe said the highest goal humans can achieve is amazement, but when you think about it, amazement is a pretty low bar given the facts of the matter, namely that we live on a spinning hunk of rock in an undistinguished corner of a universe full of stars, and we haven’t the faintest idea where it all came from. How is it that we aren’t wonderstruck by existence every second of every day?

I don’t know much about Rodney Dangerfield, but I do know that this is one heck of a lede to introduce a story about the comedian:

Imagine having no talent. Imagine being no good at all at something and doing it anyway. Then, after nine years, failing at it and giving it up in disgust and moving to Englewood, N.J., and selling aluminum siding. And then, years later, trying the thing again, though it wrecks your marriage, and failing again. And eventually making a meticulous study of the thing and figuring out that, by eliminating every extraneous element, you could isolate what makes it work and just do that. And then, after becoming better at it than anyone who had ever done it, realizing that maybe you didn’t need the talent. That maybe its absence was a gift.

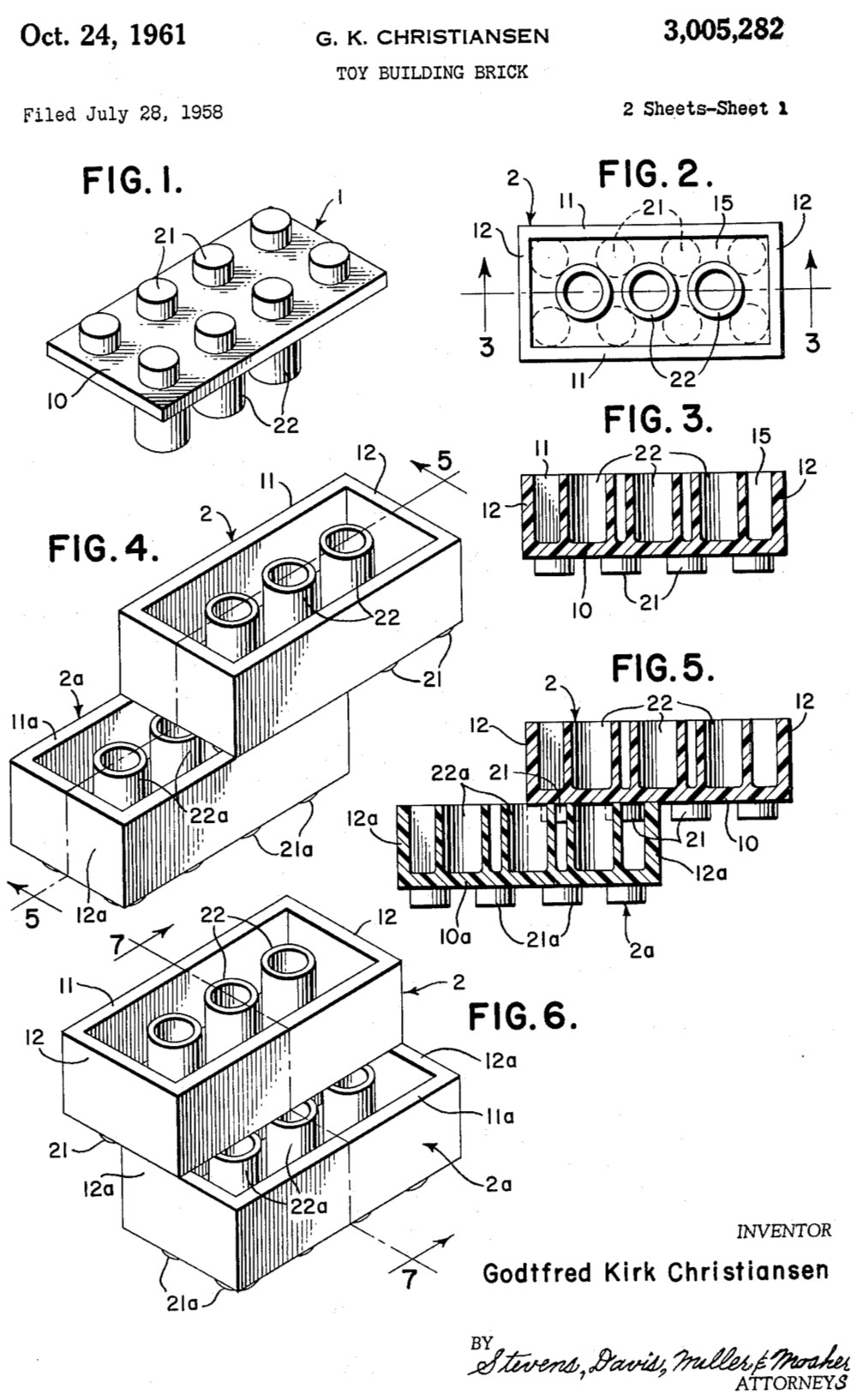

A fun blast from the past, via Kottke: the original US patent drawing for the Lego brick, filed 60 years ago:

I know it’s an ad for Apple, but this short film, Three Minutes, is heartwarming and beautiful and worth spending seven minutes to watch.

And a few more:

- Justin Timberlake and the fall of the mediocre man

- The farce, and the grandeur, of Black History Month under Trump

- All followers are fake followers

- Canada now has a gender neutral national anthem

- Why menu translations go terribly wrong

- Baby boomers are killing the early bird special

- Decoding the design of in-flight seat belts

- 9 things people with high-functioning depression want you to know

- I haven’t seen the movie, but I have a controversial opinion about it anyway

Have you had the chance to read the first issue of The Disconnect yet? If not, head on over to their site, turn off your wifi and put your phone on airplane mode, and enjoy some great writing.

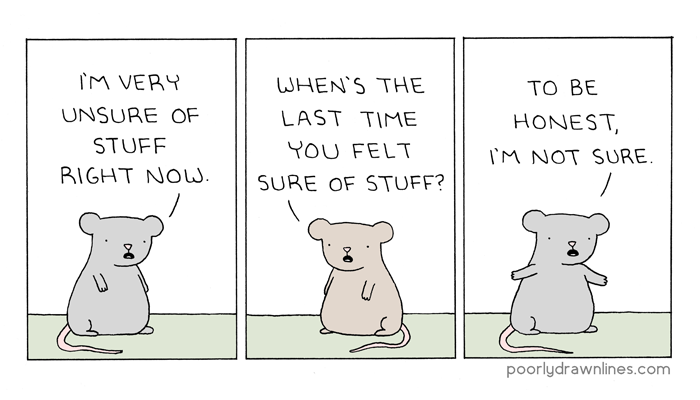

And before you go, a PoorlyDrawnLines comic strip that describes almost perfectly how I’ve been feeling recently:

Want to get this and future weekend reading links in your inbox instead of checking the blog? You can now subscribe to the newsletter.