Memory is the muscle sting of now

I have been doing David Chariandy’s Brother an immense disservice when I refer to it as a novel. There is a lyricism, a volume, a pulsating rhythm through every word Chariandy writes: Brother is more song than novel.

The first time I read Brother, three words jumped out at me: violence, viscerality, and volume.

The violence in the story is both evident—in the beatings, the shootings, the jars of pickles breaking against the wall—and subtle: violence is hidden in the way the Michael and Francis perceive the world, in the way the world sees them. No one is ever calm, or at ease; living on the edge is trauma in itself.

Chariandy’s words, his lyrics of this song, are more than just sonorous; they are palpable. We feel each gaze upon the boys as if someone was gazing upon us, and we feel the knife blade in our own hands as Francis grabs it to protect his brother. Every setting, every circumstance is visceral. From the start, I felt dampness as if I had been sprayed by slush just minutes before.

Dionne Brand describes Brother as “timbrous.” Marlon James says it is “pulsing with rhythm, beating with life.” The words are sonorous, but they are also loud. Chariandy infuses the entire story with music, but every word has volume: the sirens of the police cars, the ruffles of pages of books at the public library.

The second time I read Brother, I felt in it a story of grief. The book is an elegy to a lost brother, but it is about so much more loss. It is about the loss of innocence, about the loss of comfort, about the loss of community. It is a story of grief, of coming to terms that the world does not always cooperate and that we often lose what we had hoped and envisioned and must just take what we are given. We grieve those hopes and visions, we grieve the loss of lives we could have had. It is about complicated grief, but also a traumatic grief: it is not just a grief based on loss that lingers, but a grief that is reinforced every day by the trauma we face because of who we are.

The third time I read Brother, I felt in it a story of manhood. The story is filled with performative masculinity—most poignantly when Anton, after being beaten, turns his crying into laughter—and with the complicated dance of knowing what it is to be a man. Is masculinity performed, or felt? Is it seen, or perceived? What does it mean to be a man when nobody ever taught you how? What does it mean to be a man when you don’t know from whom to learn?

The fourth time I read Brother, I sang each word.

Chariandy’s tale of growing up in Scarborough is song as memory. It is a lyrical, melodious, melancholic reverie passing through time to evoke memory through stories.

Memory is “the muscle sting of now.” Brother is that sonorous hum through those muscles. And so, I sing. Volume!, I say.

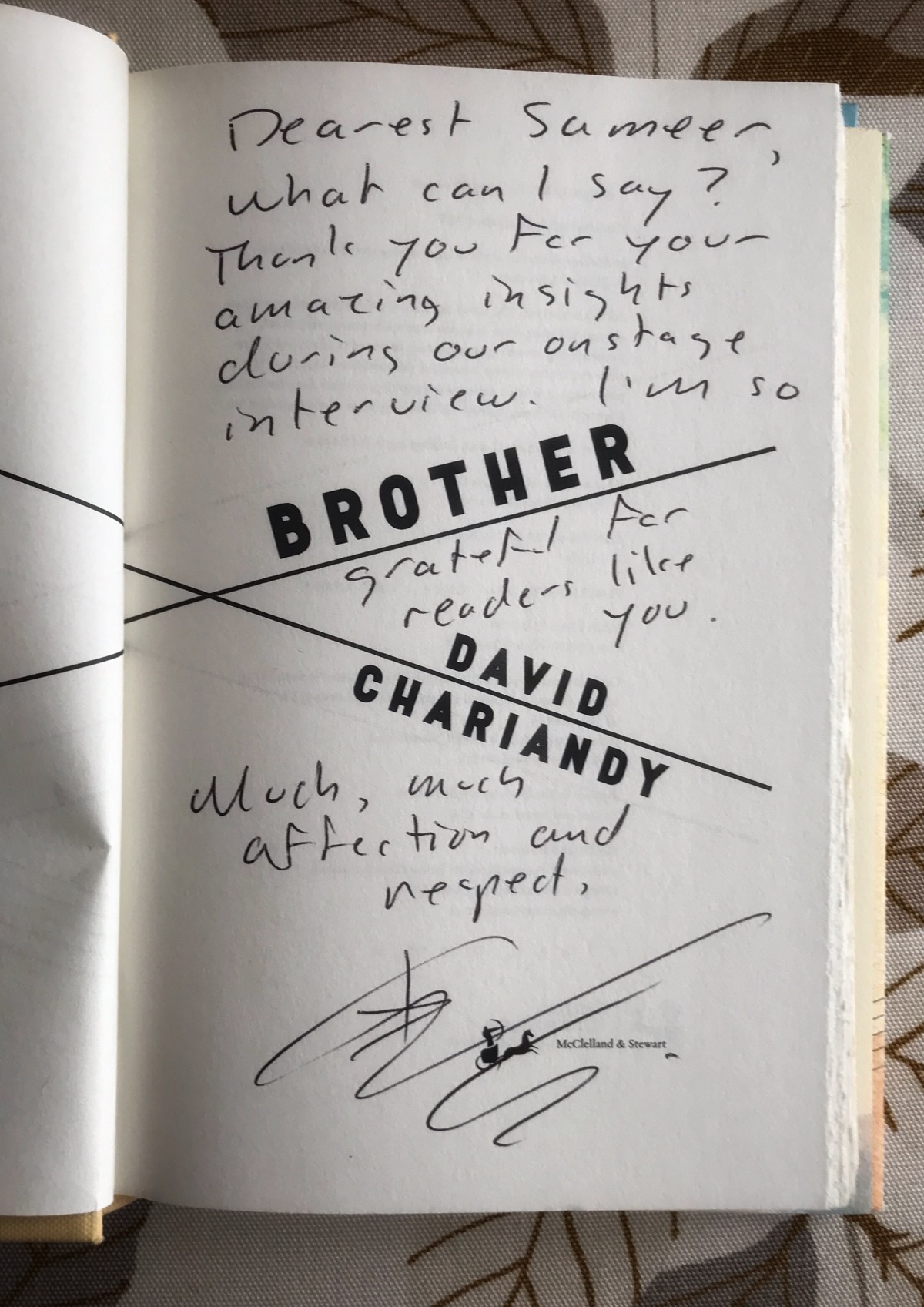

(I will be hosting a chat with David Chariandy at the Wolf Performance Hall on Monday, April 16, 2018 at 7pm as part of the One Book One London initiative. In our chat, we’ll be discussing some of the things I wrote about above; if you’re in London and have a free evening, please do come out and join us.)