Yangjin’s boardinghouse

It was when I first moved out, at the age of 17, that I felt truly independent.

In many ways, I was still dependent on my parents, but the act of having a place of my own, a room of my own—even if it was shared with three other people my age—helped me feel like I had finally grown up, like I had finally made it.

The current struggle for affordable housing in our cities has made it almost impossible for many people to find that independence, to have space of their own.

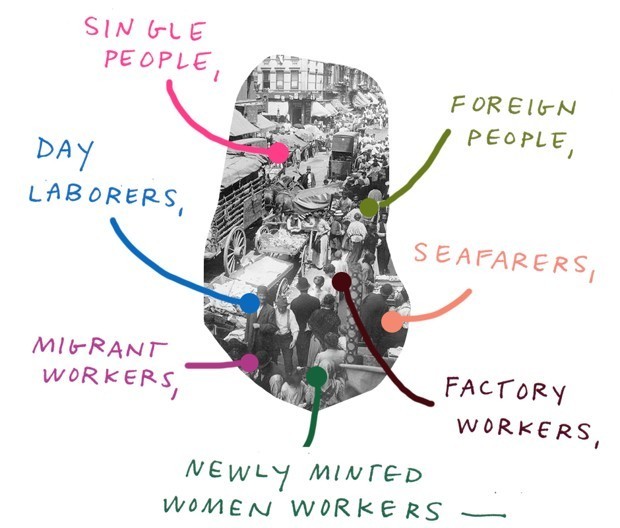

A few weeks ago, I learned that this housing crisis has a lot to do with the elimination of flexible housing stock after World War II. Prior to that, housing in America’s cities was more fluid, flexible, and communal; the bed, not the house, was the basic unit of a home. The rise of the “single family home” as a housing unit decimated urban housing stock and led to some of the issues we face today.

Of the many things I learned in Ariel Aberg-Riger’s visual story on single-room occupancy housing, what really resonated was the independence that this kind of flexible housing offered to women:

Living with the bed as the unit meant that housewives renting out rooms often had more reliable income than their husbands, single workers (especially women) could work without the crushing burden of housework, the Great Depression’s “newly poor” could keep a roof over their head as they tried to claw their way back up, and everyone who wanted (or needed) could shed personal living rooms and even kitchens and bathrooms in order to live closer to the downtown and adopt it as an outflow of their “home.”

I though of Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko quite a bit as I ruminated on the idea of boarding houses offering independence to those who would not normally be able to afford that agency. Yangjin’s boardinghouse allows her to care for her children, to build a family and a community after her husband passes away. She is tied to the place, but she is not beholden to it.

Pachinko is, in many ways, a story about the desire for independence: whether it be Sunja selling her prized possessions to pay back debts, Kyunghee and Sunja selling kimchi at the market, or Noa shunning his family to be free of unwanted legacy, the story is driven by the desire for independence, for a space—physical, emotional, and metaphorical—of one’s own.

And so, I keep coming back to Yangjin and her boardinghouse. What opportunities did she have, did her family have, because she was able to run and share a home? What agency did she provide others, her boarders, by providing them a home where they otherwise may not have been able to afford one?

How has our obsession with the suburban single-family home affected the notion of independence and individual agency? How can we fix this?

Questions to which I have no answers, but very much worth asking.