Letters of note, letters as acts of faith, letters as our truest selves

I was in the stationery store this afternoon, stocking up on cards and letter paper, and the woman behind the counter asked me what I planned to do with all my purchases. I responded, surprised that there was any other option, that I planned to ”send letters to friends, of course.”

It turns out that this was not a customary response, and the woman behind the counter went on to ask me about my epistolary habits at length. Anyone who knows me well knows that I send letters, between 300 and 400 a year, to friends and loved ones; I was glad to share the details of that habit with this woman who seemed delighted to hear it all.

In Solitude, Michael Harris spends an entire chapter writing about letters; since reading it, I have been thinking a lot about why I love to send correspondence in the post, and why this has been the one habit of mine I have kept going since my childhood. There are, of course, many answers to this question, but one of them is clearly that I love the process of letter-writing. I love what it evokes inside me, I love what it makes me feel about the person I am writing to, and I love how it acts as this quasi-spiritual bridge between us, and between our inner lives.

Harris summed it up pretty well in his book:

A letter is an act of faith—the solitary letter writer, working for hours, perhaps, at a single expression from one human heart to another, must assume a connection to someone who is absent and non-responsive for maybe weeks at a time. As the critic Vivian Gornick has it: “To write a letter is to be alone with my thoughts in the conjured presence of another person. I keep myself imaginative company. I occupy the empty room. I alone infuse the silence.” One presses beyond the happenstance of spoken speech (and the casual reassurances of texting and email) into an ordered expression of things that requires removal from chatter. And yet that conjured person does sit by our side. When we take the time to write long letters to those we care about, we uncover a part of them that was not revealed before, not at dinner parties, nor cafés, nor even lying together in rumpled sheets.

I write letters as small acts of faith, as little nuggets of hope and brightness in a world that can so often feel dark and despondent.

On the plane, on the way here to Seattle, I watched Can You Ever Forgive Me?, a film based on the true story of letter-forger Lee Israel. The movie was charming in many ways, but one part still stays with me: a conversation about the delight of having someone keep your letters much after you’ve passed on, and people clamouring to buy them as collector’s items.

I have written thousands of letters in my lifetime, and I can guess that fewer than 1% of them have been kept. I can also guess that fewer than 1% of those that were kept are actually worth keeping. For the most part, my letters are not momentous: they are missives that detail my spirit, that recount my everyday life. I am not interesting—nor famous—enough for anyone to care about my letters once I am gone.

I am curious, however: what makes a letter valuable? What makes someone want to collect the words of another, words that were destined for yet another stranger to the collector? In the film, the forged letters are often just good encapsulations of the voice and tone of the writer, but the ones that fetch the most money are filled with enticing, often salacious, content. If a letter is but a retelling of our spirit and our life, and if our life is mired in the mundane, what is there worth to keep?

These thoughts, about the noteworthiness of letters, have particularly been on my mind after reading pieces on three separate historical letters, recently. The first, where Dame Emma Thompson resigns from a film that she wanted to do, with a director she liked, because John Lasseter had joined the production company, says what so many of us have been thinking in the #MeToo era:

Much has been said about giving John Lasseter a “second chance.” But he is presumably being paid millions of dollars to receive that second chance. How much money are the employees at Skydance being paid to GIVE him that second chance?

Why is this a letter that will be noteworthy in the years to come? Perhaps it is because the letter speaks a truth that so many want to say, but don’t have the ability or position to voice. As Mary McNamara says in her analysis of Dame Thompson’s letter:

Thompson walked away from a film she wanted to do and a director with whom she wanted to work because “no” means “no,” and it needed to be said in terms that Hollywood can understand.

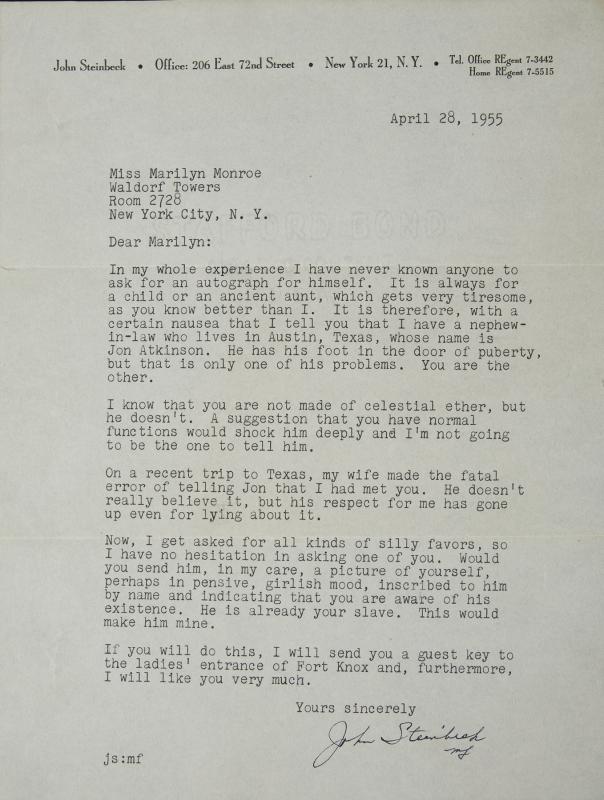

Another, John Steinbeck’s letter asking Marilyn Monroe for her autograph for his nephew, is memorable and collector-worthy not because it is the voice of the many, but because it is the singular voice of one, quirky and strange and honest and delightful:

I know that you are not made of celestial ether, but he doesn’t. A suggestion that you have normal functions would shock him deeply and I’m not going to be the one to tell him.

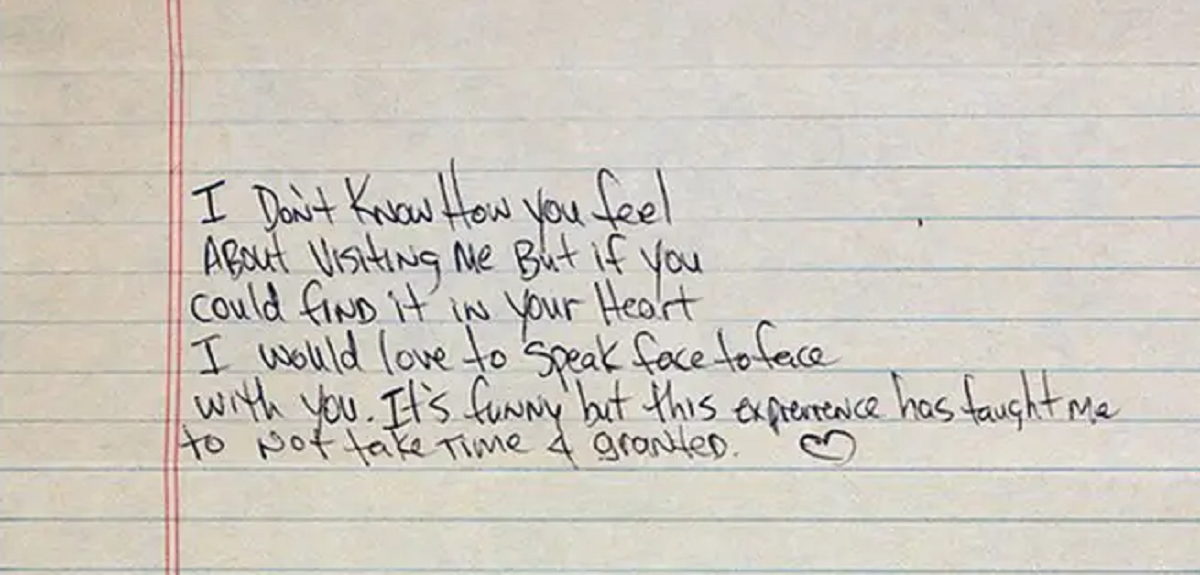

The letter of note that has weighed most heavy on my heart is one of matters of the heart: Tupac’s apology to Madonna, after their breakup, written while incarcerated. I, too, have written apology letters—to friends, strangers, and loved ones—and feel the raw honesty in his letter most deeply. Few, if any, have had this kind of emotional release.

Chandra Steele sums up one of the most striking parts of the letter:

The letter is, above all else, generous. Even when he mentions an egregious comment Madonna made in an interview — “I’m off to rehabilitate all the rappers and basketball players” — he does so only to elucidate that the words were a blow to his heart and ego that resulted in his saying things he came to regret.

What’s more remarkable than what’s written is what isn’t. Tupac does not overstep the bounds of being an ex-lover. He does not push a selfish agenda. He has the wisdom to balance what he wants with what is warranted after leaving sans explanation. He does not burden her by asking for her forgiveness.

There are many reasons why one would want to collect this letter by Tupac, but I hope that instead of a collector, the letter was returned to its recipient. This kind of emotional catharsis feels too personal to be held by someone to whom it was not addressed. The letter is most noteworthy because it should not be public, but instead held in confidence between the hearts of lovers.

The appeal of Lee Israel’s forgeries, at least according to Can You Ever Forgive Me?, make sense to me only when I realize that sometimes the only way to understand the spirit of someone is through their correspondence. If a letter is how we share our thoughts, feelings, vulnerabilities, and mundanity, then a letter approaches being a representation of our truest selves.

Michael Harris, in Solitude, sums it up nicely in two sentences:

In the solitary composition of our love letters we heal wounds and bridge distances. When we write them we experience communion within our solitude.

I did not say all of this to the woman behind the counter at the stationery store, but I did tell her of the joy that putting a pen to paper, and then sending that paper via the post, brings to me. In telling her this, I realized that in my letters, I am my truest self, and I know myself best. I left the store feeling hopeful, and ready to send more correspondence.