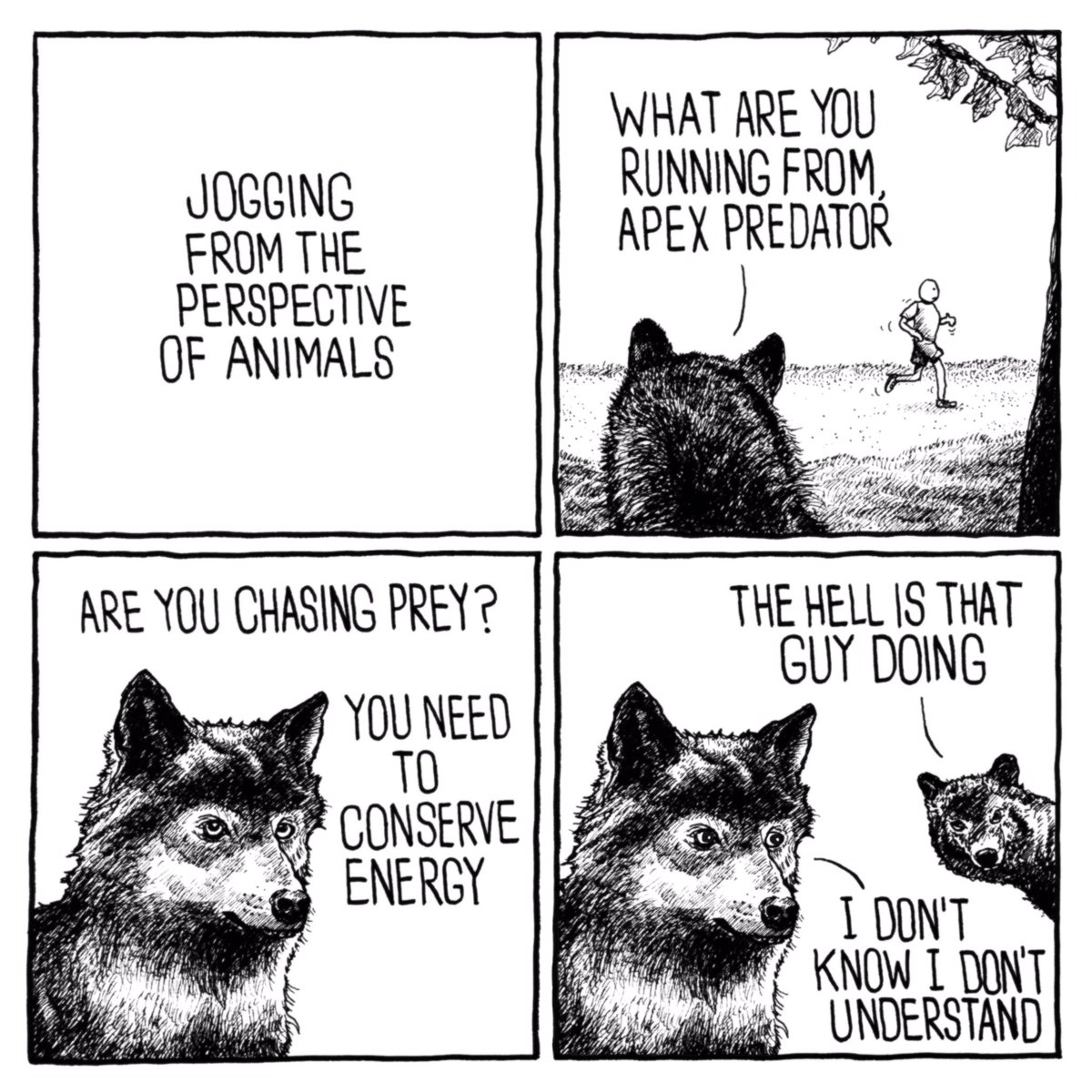

Going for a jog.

There are many things that baffle me. For years, one thing I could never understand were runners: what motivates people to put on special shoes early in the morning on a cold day just to run in a circle and come home again?

Running is something that never really made sense to me, but a large part of that bafflement came from the sheer pain I would experience when I attempted to run. Why would anyone decide to live through that pain?

In hindsight, I should have realized that not everyone experienced crippling pain when they ran. My weight made even walking difficult, and my barely-held-together knee was in constant pain even when I was just standing up; this was not the experience of the average runner.

These days, my knee is feeling a lot better. My weight is still high, but my body composition has changed enough that it no longer hurts to walk.

A few weeks ago, I became fixated with the idea of taking a jog. I’m not sure what caused that fixation, but all I could think about was what it would take for me to go for a run, even if it was for just a few minutes.

I found a Couch to 5K app for my phone; I’m on week 2 of the program now, and while it hasn’t been easy (my legs ache every day), it hasn’t been terrible. In fact, using the app and starting to jog has actually been fun.

I’m not sure how long I’ll stick with it — my goal is to complete the entire 8-week program — or if this will turn into a regular running practice, but for now, I’m enjoying doing something I’ve never done before. I’m running (slowly, of course) and feel great about it.

Slowly, I’m starting to understand why people run, why they wake up obscenely early and pull on special shoes, no matter how cold the day. That’s how it goes, often: you only understand the motivations of others when you try spending a day (or eight weeks) in their (running) shoes.

A few things to read and explore:

Why Bureaucrats Don’t Seem to Care, Bernardo Zacka:

The personal tragedies that result from public-policy choices—the clients who fall between the cracks; those who need help but cannot get it—are incidents that ordinary citizens might have the luxury to ignore. For frontline bureaucrats, however, this is the stuff of everyday work. In a democracy, these bureaucrats make hard decisions in the name of citizens so that the latter do not have to.

If bureaucrats appear distant and unconcerned, if they seem cold and expressionless, it is important to remember that they are like that in part because of the policy choices that were made by their fellow citizens through the democratic process, and the meager resources that were placed at their disposal. To express sympathy for bureaucrats is not to condone the system of public assistance they represent, but to acknowledge that it does not leave them unscathed either.

One person’s history of Twitter, from beginning to end, Mike Monteiro:

There was a time where Twitter was a place you went to fuck around, and accidentally made friends and got smarter. It’s been years since I’ve felt smarter after being exposed to Twitter, but trust me, those days were real. They happened. […}

Like Oppenheimer, Twitter was so obsessed with splitting the atom they never stopped to think what we’d do with it.

Twitter, which was conceived and built by a room of privileged white boys (some of them my friends!), never considered the possibility that they were building a bomb. To this day, Jack Dorsey doesn’t realize the size of the bomb he’s sitting on. Or if he does, he believes it’s metaphorical. It’s not. He is utterly unprepared for the burden he’s found himself responsible for.

The power of Oppenheimer-wide destruction is in the hands of entitled men-children, cuddled runts, who aim not to enhance human communication, but to build themselves a digital substitute for physical contact with members of the species who were unlike them. And it should scare you.

The Men You Meet Making Movies, Sarah Polley:

I want to believe that the intense wave of disgust at this sort of behavior will lead to real change. I have to think that many people in high places will be a little more careful. But I hope that when this moment of noisy sisterhood dissipates, it doesn’t end with a woman in a courtroom, being made to look crazy, as these stories so often do.

I hope that the ways in which women are degraded, both obvious and subtle, begin to seem like a thing of the past.

For that to happen, I think we need to look at what scares us the most. We need to look at ourselves. What have we been willing to accept, out of fear, helplessness, a sense that things can’t be changed? What else are we turning a blind eye to, in all aspects of our lives? What else have we accepted that, somewhere within us, we know is deeply unacceptable? And what now will we do about it?

This Was Always Going to Hurt, Katie McDonough:

One of the more subtly nauseating things Harvey Weinstein, the disgraced studio director and serial abuser, has leaned on in these last weeks is this claim to “therapy.” He will get help, he says. Do hard thinking before returning, triumphantly, to win more Oscars. As a colleague commented to me the other day, this is rich people speak for fucking off for a few months. But I also believe that a restorative mediation process of the sort that has been specifically designed (and practiced) for abusers is necessary if the violence is going to stop. It’s another place where I don’t have great answers. But if the option is that or nothing, I don’t believe we can choose nothing.

But there are also ways to make formal channels of reporting more accountable so that women may feel more comfortable pursuing them in certain cases, since there is no single method of redress that will work every time and for every woman. Are the managers who saw their employees’ names on the list going to address the existence of allegations internally? Are colleagues talking about unionizing as a means of holding management accountable? Are union members meeting to discuss and update processes around reporting, investigation, and protection? Are companies considering what mechanisms exist for people to come forward if they experience harassment or abuse? Are these same companies interrogating what happens with those complaints if they are filed?

This week has been an agonizing reminder that laws and policies against harassment mean nothing if they are not vigilantly enforced and interrogated for their efficacy. But it’s also been an uncomfortable moment to ask ourselves what we believe should happen to abusers if they are, in rare instances, exposed.

I Have Been Raped by Far Nicer Men Than You, Natalie Degraffinried:

If you decide to be a feminist after a life of being forced to be around and to idolize men, you start to play a fucked-up game of six degrees of separation from imaginary rapists that men you know may or may not be associated with—you have to, to some extent, and you have to do it quietly because, inasmuch as men deny the reality of sexism, they will find you crazy and paranoid for assuming that anyone could rape you.

It’s amazing, really—men constantly place the burden of not being raped on women and then react negatively to measures women take to do just that if they seem extreme. But the thing is—just like a healthy mistrust of any group wielding institutional power—the “extremes” we go to are still not sufficient.

We must be dazzlingly, dangerously close to being raped before it actually becomes something to call out—the shadows dancing in your eyes after a round of drugs slipped into your drink, the chorus line of women kicking and flailing out of silence into a media firestorm, the flash and bang of broken objects on the off chance you are not paralyzed by the relationship you and the rapist have.

And then it still isn’t enough.

In the U.S.’s debate over free-speech politics, Black Americans lose, Andray Domise:

Where Black identity is concerned, all speech is political speech. In a social environment where principals suspend students, coaches expel players, and spectators are confident shouting slurs and dumping beer on the heads of silent protesters (in an eerily similar fashion to the pro-segregationists who showed up to the Woolworth’s lunch counter to remind integrationists just who was in charge), Black people and public figures find themselves in the exact double-bind Jemele Hill described. When other Black Americans face state-sanctioned violence and injustice, does one choose their profession and education, and even their personal safety? Or should they choose the community they represent?

@20, Paul Ford:

Our software is bullshit, our literary essays are too long, the good editors all quit or got fired, hardly anyone is experimenting with form in a way that wakes me up, the IDEs haven’t caught up with the 1970s, the R&D budgets are weak, the little zines are badly edited, the tweets are poor, the short stories make no sense, people still care too much about magazines, the Facebook posts are nightmares, LinkedIn has ruined capitalism, and the big tech companies that have arisen are exhausting, lumbering gold-thirsty kraken that swim around with sour looks on their face wondering why we won’t just give them all our gold and save the time. With every flap of their terrible fins they squash another good idea in the interest of consolidating pablum into a single database, the better to jam it down our mental baby duck feeding tubes in order to make even more of the cognitive paté that Silicon Valley is at pains to proclaim a delicacy. Social media is veal calves being served tasty veal. In the spirit of this thing I won’t be editing this paragraph.

A gorgeous photo of Union Station, Chicago, taken by Esther Bubley in 1948:

And a few more: