Sparkles in the snow

Some nights, when we look outside onto the front yard as part of Z’s bedtime routine, the snow shimmers in the moonlight, as if someone had dropped a jar of sparkles all over the yard. The sight is fleeting, beautiful, and peaceful; we search for this sparkly snow every night, and exclaim with glee on the nights when we manage to see the shimmer across the front of the house.

It hasn’t been the easiest of months: the cold is biting and while we make it a point to go for a walk outside almost every day, the weather makes it difficult to enjoy the outdoors as much as we would like. The cold, coupled with the lockdown because of the pandemic, has left us mostly isolated; we see each other—and I am thankful to be able to spend all my time with the two people (L and Z) I love most in the world—but nobody else, and this isolation can often feel oppressive. February is a hard month in the best of times, and this year is no exception.

During the hard times, the difficult months, we find solace in small joys: the chocolate delivered to our door, the way Z laughs when we blow on her belly, the kind letters sent to us from friends afar, our cold but sunny walks in the park, a cup of tea in the afternoon, the shimmer of the snow when the moon is out and the yard is full of sparkles. February will pass soon; the spring is on its way and with it more sunshine, more warmth, more time outside, hopefully a few glimpses of friends and family (when we can safely see them outdoors), and a rejuvenation of the spirit that echoes the rejuvenation of nature.

In the meantime, every night, we look out for the sparkles in the snow. And every night we remember just how lucky we are to be able to enjoy this shimmer in the moonlight with the people we love most.

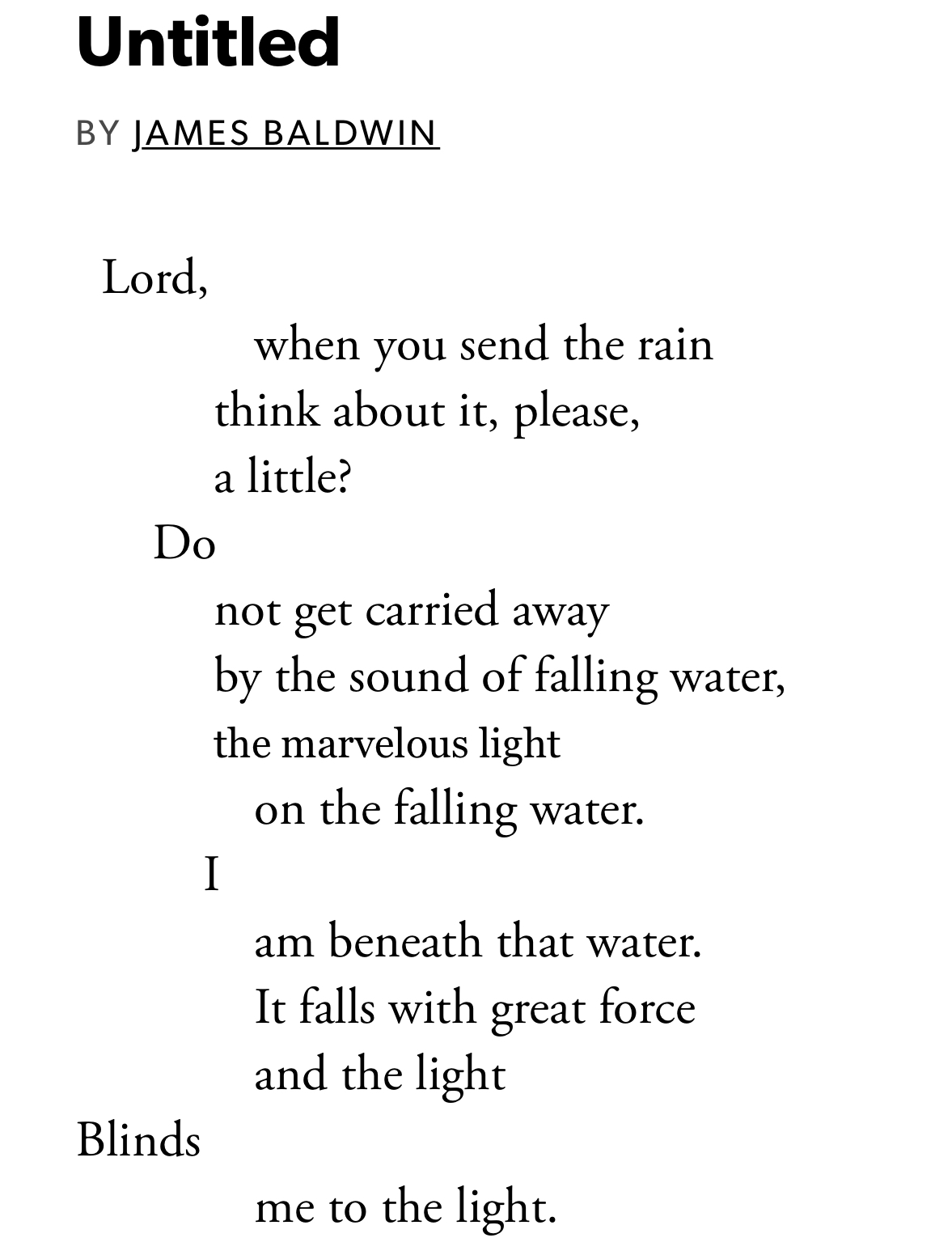

Two poems

The Good News

Thich Nhat Hanh

They don’t publish

the good news.

The good news is published

by us.

We have a special edition every moment,

and we need you to read it.

The good news is that you are alive,

and the linden tree is still there,

standing firm in the harsh Winter.

The good news is that you have wonderful eyes

to touch the blue sky.

The good news is that your child is there before you,

and your arms are available:

hugging is possible.

They only print what is wrong.

Look at each of our special editions.

We always offer the things that are not wrong.

We want you to benefit from them

and help protect them.

The dandelion is there by the sidewalk,

smiling its wondrous smile,

singing the song of eternity.

Listen! You have ears that can hear it.

Bow your head.

Listen to it.

Leave behind the world of sorrow

and preoccupation

and get free.

The

latest good news

is that you can do it.

Some links

We need poetry more now than ever. These are some excellent poems for a new year.

We need to rethink political journalism. This piece is a good start to thinking about how the industry can change itself:

First of all, we’re going to rebrand you. Effective today, you are no longer political reporters (and editors); you are government reporters (and editors). That’s an important distinction, because it frees you to cover what is happening in Washington in the context of whether it is serving the people well, rather than which party is winning.

Historically, we have allowed our political journalism to be framed by the two parties. That has always created huge distortions, but never like it does today. Two-party framing limits us to covering what the leaders of those two sides consider in their interests. And, because it is appropriately not our job to take sides in partisan politics, we have felt an obligation to treat them both more or less equally.

Wikipedia introduced a universal code of conduct recently. I’m proud to have spearheaded the creation of our code of conduct at work some years ago; it’s the framework for how we work together. Good on Wikipedia for doing this.

An impressive collection of pandemic graphics. How we communicate to each other in this time of tumult is fascinating.

Restaurants have been facing a reckoning since the pandemic started. How did we get here, and what’s next?

The figure of the chef-tyrant satisfied something deep in the id of the food media, and perhaps of the political-media establishment as a whole: after all, Bourdain, Ramsay, and their ilk rose to fame at the dawn of the never-ending war on terror. At the same time, glorification of kitchen cruelty ratified a profoundly shitty reality for all the cooks, dishwashers, servers, and food runners who, already scraping to survive on appallingly low pay, had to suffer under a whole generation of chef-bosses, almost all of them men, encouraged to see their personality defects as marks of unalterable genius. And public righteousness was no guarantee that a restaurant had shaken free of the industry’s pathologies. Of the “virtuous” restaurants that proliferated across America during the pre-Covid years—establishments offering healthy, bright, organic, humane flavors on the plate, and progressive politics on the Instagram grid—perhaps none was more popular than Sqirl, which Eater once described “the indie star of LA’s restaurant scene.” In recent months, however, the moldy truth emerged: the restaurant made famous for its ricotta toast and for serving food “both virtuous and delicious” (Eater again) was in fact a black site of manipulation, abuse, and crimes against jam.

A brief history of flight attendants and how they are coping with the pandemic and their changing work environment—an environment that has been constantly changing through the years, not just during the pandemic.

An interesting argument for why America should move to the parliamentary system and why Joe Biden should be the last president.

I’ve had a few times that could be considered nervous breakdowns in my past, and have emerged stronger and better. Why have we forsaken the nervous breakdown as a reason to escape and rejuvenate?

For 80 years or so, proclaiming that you were having a nervous breakdown was a legitimized way of declaring a sort of temporary emotional bankruptcy in the face of modern life’s stresses. John D. Rockefeller Jr., Jane Addams, and Max Weber all had acknowledged “breakdowns,” and reemerged to do their best work. Provided you had the means—a rather big proviso—announcing a nervous breakdown gave you license to withdraw, claiming an excess of industry or sensitivity or some other virtue. And crucially, it focused the cause of distress on the outside world and its unmeetable demands. You weren’t crazy; the world was. As a 1947 headline in the New York Herald Tribune put it: “Modern World Viewed as Too Much for Man.”

“A workplace has its own informal cardinal directions: elevatorward, kitchenward, bathroomward. It’s a map we share.” I think a lot about work offices these days, now that I haven’t worked in one for five years.

We loved going to Ample Hills last time we were in Brooklyn, but it looks like the company has been in trouble for a very long time now, well before the pandemic.

I am fascinated by this piece on diamonds and marriage and love and everything in between:

We’ve coupled love to marriage and we’ve coupled marriage to diamonds, and all three thrive on the assumption of rarity. What would it mean for love to be common? For marriage to become irrelevant as its benefits are made available to all? I say this as someone in love and in a marriage, who gets fiercely defensive of those things. But I could easily have married my college boyfriend if the terroir were right. I could have married anyone, which is not something I’m supposed to think about. We know that love is not perfect, that it’s arbitrary and common, that if we grew up a state away or spoke a different language, we might not have fallen in love with the person we currently love. But to admit that would be to break the spell and rebuild our relationships on … what exactly? I don’t know how to value things if they are not unique. I don’t know how to care about something if it’s not special, and though I feel like my relationship is the only one of its kind, I don’t know why that is.

I never had the “lunchbox moment” growing up, and was always happy when I got foods from my culture in my lunchbox as a child. The lunchbox moment is a trope of popular culture that never resonated with me, and I’m glad I’m not the only one.

“What pushes people out into the street and what pushes them to organize might be sparked in a single moment, but before that moment, and often stretching on long after, is a series of small collapses caused by continual neglect.”